Dies Irae: Specters of The Dead in Late 19th & Early 20th-Century Instrumental Music

Alice Ivy-Pemberton

The Dies irae sequence from the Roman Catholic Mass for the Dead (also known as the Requiem) is an iconic, oft-quoted fragment of medieval music. The poem itself is also medieval (written in the Latin of the Middle Ages) and was long ascribed to the Franciscan monk Thomas of Celano (d. c. 1250); however, its origins have since been traced to an earlier version of the text from the twelfth century. It is still unknown who composed the melody of the Dies irae and when it was composed, although some scholars have suggested the mid-twelfth century as a possible date.[1] Within the liturgical upheaval and far-reaching reforms of the sixteenth-century Council of Trent, the text of the Roman Catholic Requiem was standardized, and all but four of the numerous sequence hymns and tropes which had been added to the Mass in the preceding centuries were abolished.[2] However, the very last piece to survive the Tridentine reforms and be added to the Requiem and permanently incorporated into the liturgy was the Dies irae sequence, which stands apart from the texts of the orthodox tradition because of its vivid and apocalyptic evocation of the Biblical Judgment Day[3]:

Dies irae, dies illa, Day of wrath, that day

Solvet saeclum in favilla Will dissolve the earth into ashes

Teste David cum Sibilla. As David and the Sibyl testify.

The chant itself is not as musically appealing as other sequence hymns, with a low tessitura and restricted range, but it is nevertheless an extremely potent musical vehicle for the dark atmosphere and doomsday character of the poem.[4] Robin Gregory’s 1953 article in Music & Letters entitled “Dies Irae,” quotes St. Bernard of Clairvaux on the extra-musical requirements of plainchant: “Let the chant be full of gravity; let it be neither too worldly, nor too rude and poor…. Let it move the heart. It should not contradict the sense of the words, but rather enhance it.”[5] As Gregory describes, the Dies irae theme does just that, with its ability to provoke a powerful sense of awe (one might say of Biblical proportions) even today, nearly nine hundred years after its origins.

Although the original text of the Dies irae is certainly foreboding with its “graphic portrayal of the Day of Judgement,” it was through a “process of gradual assimilation in secular music [that] the terror of Celano’s last judgement has become more generalized, and the melody has acquired connotations of malevolence, devilry, and witchcraft, which have no place in the original text,” as Malcolm Boyd states in his article “Dies Irae: Some Recent Manifestations,” [6] It is with these associations in mind and with a broader understanding of the Romantic and late-Romantic interest in the supernatural, the fantastic, and the macabre that much of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries’ secular uses of the Dies irae have been interpreted and analyzed.[7] In this essay, I wish to explore three very different references to the Dies irae in works by Ysaÿe, Rachmaninoff, and Brahms that nevertheless are bound together in their use of the theme as a vessel for expression of the ghostly, diabolical mysticism of death and the dead. The works considered here are Ysaÿe’s Sonata No. 2 from his Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, Op. 27 (1923), Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op. 43 (1934), and Brahms’ Intermezzo in Eb minor, Op. 118 No. 6 (1893).

Eugène Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin, Op. 27 are a landmark of the unaccompanied violin repertoire, and were modeled by the composer after the Six Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin by J.S. Bach after a bout of inspiration upon hearing Joseph Szigeti play one of the Partitas in 1923. Ysaÿe seemed to understand the enormity of this undertaking, and is quoted as saying “The genius of Bach frightens one who would like to compose in the medium of his sonatas and partitas. These works represent a summit and there is never a question of rising above it.”[8] While all six sonatas are still frequently studied and performed today, there are two which have attained a popularity beyond the other four: Sonata No. 3, The “Enesco,” and Sonata No. 2, The “Thibaud,” which is the subject of my discussion here and, tellingly, the only sonata of the six with an explicit subtitle, which is “OBSESSION,” written “in heavy type.” [9] (Each sonata is dedicated and modeled after the violin playing of a virtuoso of Ysaÿe’s time.) The “Obsession” sonata does not appear on many academic lists of Dies irae references in secular music, including Boyd’s and Gregory’s, despite its explicit and varied use of the theme throughout the work’s four movements. Indeed, despite having more nuance and variations in character, Ysaÿe’s use of the plainchant is nearly as overwhelming and thematically crucial as Liszt’s use of the sequence in his Totentanz.

Ysaÿe’s Sonata No. 2 begins, almost insolently, with a direct quotation from Bach’s Preludio from Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006. This fragment, “set out in small notes to indicate that it is to be played sotto voce, as if heard from a distance,” reflects Ysaÿe well-documented and lifelong “obsession” with J.S. Bach and his inability to escape the specter of Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas while composing his own Six Sonatas.[10] After playing this quotation in the first movement, entitled “Prelude: Poco Vivace,” the violin suddenly and violently breaks away from Bach and “launches itself into a kind of rage, as if in fierce combat.”[11] It is within this clash of titans--between Bach’s motives as an almost diabolical force and Ysaÿe’s virtuosic attempts to escape them--that the Dies irae first emerges.

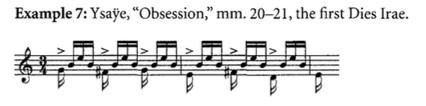

There are even deeper resonances between Ysaÿe’s “Obsession” (and statements of the Dies irae) and Bach’s “Preludio,” extending into the very nature of the violinistic technique the composers use. In “Becoming Bach, Blaspheming Bach: Kinesthetic Knowledge and Embodied Music Theory in Ysaÿe’s ‘Obsession’ for Solo Violin,” Mary Lee Greitzer imaginatively details particular technical similarities between the “Preludio” and the first statement of the Dies irae in the “Obsession” sonata.[12] As Greitzer describes, there is a specific “bariolage” technique of rapid string-crossing in the right hand to achieve a unique arpeggiation and resonance that is often first learned by violinists in the Bach “Preludio” which is also used quite forcefully by Ysaÿe in mm. 20-21 of the first movement of “Obsession” to state the Dies irae (see fig. 1 and fig. 2).[13]

fig. 1

fig. 2

Greitzer claims (and I completely agree, having studied both works myself) that although the listener may not connect this “bariolaged” Dies irae to the Bach Preludio, the violinist who is performing “Obsession” will immediately intuit the link between the two passages because of their visual and physical similarities. Taking this one step further, she writes “by crafting this blatant devil music in a piece that speaks so much with Bach’s voice, Ysaÿe also manages to suggest that Bach himself is somehow responsible for this music….The Dies Irae can thus be heard as embodying an extraordinary flip of the entire question of possession and control.” [14] I linger on Greitzer’s analysis to convey, most importantly, the power and influence that a composer’s use and specific setting of the Dies irae can have on both audience and performer beyond a simple citation of doom or invocation of an ancient foreboding. Throughout the rest of Sonata No. 2 the Dies irae returns again and again as a form of “obsession” itself: it closes the second movement, “Malincolia,” with an unadorned statement over a pedal point (Ysaÿe even goes so far as to write this statement in breves, a form of notation first found in the 13th century)[15]; as seen in Fig. 3, it forms an integral part of the pizzicato theme and dancing variations of the third movement “Danse des Ombres,” and it ceaselessly punctuates the escalating and virtuosic violence of the fourth and final movement “Les Furies.”[16]

fig. 3: “Malincolia,” m. 24

Now I turn to another manifestation of “obsession,” which is Sergei Rachmaninoff’s lifelong use of the Dies irae theme in what seemed to be a form of motivical addiction. The Dies irae appears in his Symphony in D minor (composed 1896, premiered 1897), First Piano Sonata in D minor, Op. 28 (1907), tone poem The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 (1909), choral symphony The Bells, Op. 35 (1913), Études-tableaux Op. 39 (1916-1917), Symphony No. 3, Op. 44 in A minor (1936), Symphonic Dances Op. 45 (1942), and the subject of my focus here, Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op. 43 (1934), among others.[17] While invocations of the Dies irae are often at risk of being dismissed by scholars and audiences alike as a kind of doomsday hat-trick, it is clear that Rachmaninoff’s relationship to the medieval sequence extends far beyond superficial associations, much like Ysaÿe’s deeply personal use of the theme as an emblem of his battle with the ghost of J.S. Bach.

I’ve chosen to focus on Rhapsody for a number of reasons, including its strikingly similar allusions and extramusical associations with another specter of virtuosity and composition, Niccolo Paganini, but also because it is one of the first works written after Rachmaninoff had discovered the entirety of the Dies irae sequence. The Russian-American musicologist Joseph Yasser recalls a conversation with Rachmaninoff in 1931 which reveals the depths of the composer’s curiosity about the theme:

He began to tell me that he was very much interested in the familiar medieval chant, Dies Irae, usually known to musicians (including himself) only by its first lines, used so often in various musical works as a ‘Death theme’. However, he wished to obtain the whole music of this funeral chant, if it existed (though he wasn’t sure of this). . . .He also asked about the significance of the original Latin text of this chant. . . without offering a word of explanation for his keen interest in this.[18]

Much like Ysaÿe’s “Obsession,” Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini sharply contrasts an explicit musical quotation that has a distinctly lighthearted character, with the haunting theme of the Dies irae. In this case, the opening theme from Niccolo Paganini’s famous Caprice No. 24 for solo violin serves as the basis for the entire work and the more sinister character of the plainchant is introduced later. In both pieces the Dies irae serves as a polar opposite to the pieces’ carefree beginnings, invoking an almost visceral sense of darkness when employed. Although there is no specific program offered by Rachmaninoff from the time of Rhapsody’s initial composition, there is an evocative and telling letter written to the Russian choreographer Mikhail Fokin, almost three years after Rhapsody’s premiere, about a proposed new ballet based on the legend of Paganini: “Why not resurrect the legend about Paganini, who, for perfection in his art and for a woman, sold his soul to an evil spirit? All the variations which have the theme of Dies Irae represent the evil spirit.”[19] Rachmaninoff then goes on to detail the possible dialogue between Paganini and the evil spirit when the Dies irae is first stated in Variation VII and the ensuing struggle for his soul throughout the rest of Rhapsody.[20] With this program, imagined by Rachmaninoff himself, we again see the use of the Dies irae as a diabolical force in conversation with the ghost of a long-dead musical titan. It seems as if the archaic quality of the theme itself (evoking the distant past with its modal chant structure), when combined with its sacred and liturgical origins, give it a unique power and authority to convey the music and the spirit of the dead and the diabolical. While Boyd and Gregory are right to say that the original text of the Dies irae had “no associations with anything evil,” it is worth noting that throughout human history, religious texts were the principal authorities for who and what were to be designated “evil” in the eyes of God, and which would therefore condemned to eternal damnation.[21] When composers like Ysaÿe and Rachmaninoff created polarized works of light and dark, good and evil, as is the case with Sonata No. 2 and Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, the “Day of Wrath” chant served to signify an underlying, intensely compelling extremity on the spectrum of spirituality as the composers grappled with the spirits and phantasms that haunted their musical and personal worlds.

The third and final work which I will focus on is Johannes Brahms’s Intermezzo in Eb minor, Op. 118 No. 6. It is a radical departure from the clear declamations of the Dies irae found in the music of Ysaÿe and Rachmaninoff, and in this way it is perhaps the most spectral work of all, for the theme itself is ghostlike and fragmented, and the significance and purpose of its use is the most elusive. Despite these differences, the Intermezzo serves as a powerful example of the enduring mystery and profoundly personal sense of darkness generated when a composer even suggests the melody of the Dies irae. The opening of the Op. 118, No. 6 is striking (almost chilling, in fact) in its contrast to the typically dense, lush textures of Brahms, for the first two measures are played sotto voce by the right hand alone in a chant-like, meandering, and haunting statement. It is widely accepted that the Eb minor Intermezzo is “among Brahms’s most inscrutable compositions,” and this is undoubtedly in large part because of the enigmatic nature of this opening motive (which, in classic Brahmsian fashion, forms the basis for the progression of the rest of the piece).[22] Brahms’s use of this motive is also one of “obsession,” as he seems to relentlessly trace the contour of this first statement (which revolves around three pitches and is undeniably evocative of the Dies irae in its pitch content and melodic structure of a falling minor third) throughout the Intermezzo. As is the case with Ysaÿe’s “Obsession” Sonata and Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, the Intermezzo also strikingly juxtaposes light and dark elements, as the mournful first motive is restated in an ardent and heart-rending implied Db Major before unraveling back to its dark Eb minor origins in a moving depiction of the extremities of human emotion.[23]

Although there is no explicit reference or explanation of the likeness of this theme to the Dies irae, Paul Berry’s book Brahms Among Friends makes a remarkable and complex argument for the presence of veiled borrowing within the Eb minor Intermezzo of Robert Schumann’s Stücklein (Little Piece) from his Bunte Blätter, Op. 99. Without losing myself in the intricacies of Berry’s theory (which involves the incipits and musical quotations used by Brahms to communicate in his letters to his friend Theodor Wilhelm and his reference to the Stücklein as a way of discreetly airing the painful emotional conflicts between Brahms and Clara Schumann), it is significant to note that for Brahms, just as for Ysaÿe, the allusion to the Dies irae seems to be accompanied by the musical expression of deep personal turmoil.[24] However tenuous the connection between Brahms’s Intermezzo and Schumann’s Stucklein may be, there is an unmistakable “air of veiled significance” that pervades the piece, and a more fantastic interpretation might even say that the ghost of Robert Schumann lurks in its Eb minor depths, brought forth by this shrouded, mournful fragment of the Dies irae that conveys the pain of Brahms’s relationship with Clara.[25]

Moving from the explicit and objective citations of the Dies irae to the far more mysterious and subterranean invocations of this theme in the works of Ysaye, Rachmaninoff, and Brahms, discloses a commonality that I believe counters the pervading perception of the uses of the medieval sequence in Romantic and late-Romantic music as uniformly bombastic and emotionally superficial. What is revealed instead are the deeply personal obsessions, haunting emotions, and above all, specters of the composers’ pasts and presents that arise from this medieval chant–the Dies irae–that heralds, with sweeping universality, the coming Day of Judgment for us all.

Footnotes

[1] Robert Chase, Dies Irae: A Guide to Requiem Music (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006), 509.

[2] Robin Gregory, “Dies Irae,” Music & Letters 34, no. 2 (1953): 133.

[3] Chase, Dies Irae, 5.

[4] Malcolm Boyd, “‘Dies Irae’: Some Recent Manifestations,” Music & Letters 49, no. 4 (1968): 348.

[5] Gregory, “Dies Irae,” 134.

[6] Boyd, “Dies Irae,” 348.

[7] Gregory, “Dies Irae,” 135.

[8] Antoine Ysaÿe, Historique Des Six Sonates Pour Violon Seul Op. 27 D’Eugène Ysaÿe (Brussels: Edition Ysaÿe, 1968), 4.

[9] Ysaÿe, Historique, 8.

[10] Antoine Ysaÿe, Ysaÿe, by his son Antoine, trans. Frank Clarkson (Great Missenden, England: W. E. Hill, 1980), 141-142.

[11] Ysaÿe, Ysaÿe, by his son Antoine, 142.

[12] Mary Lee Greitzer, “Becoming Bach, Blaspheming Bach: Kinesthetic Knowledge and Embodied Music Theory in Ysaÿe’s ‘Obsession’ for Solo Violin,” Current Musicology, no. 86 (Fall 2008), 73.

[13] Figures 1 and 2 are taken from Greitzer, “Becoming Bach,” pages 72 and 73, respectively.

[14] Greitzer, “Becoming Bach,” 74.

[15] Grove Music Online, s.v. “Breve,” by John Morehen and Richard Rastall, accessed Dec. 9, 2018, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/search?q=breve&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true

[16] Ysaÿe, Historique, 9.

[17] Heejung Kang, “Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op. 43: Analysis and Discourse” (DMA diss., University of North Texas, 2004), 74-77.

[18] Boyd, “Dies Irae.” 354.

[19] Ying Zhang, “A Stylistic, Contextual and Musical Analysis of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op. 43 (DMA diss., Rice University, 2008), 12. Victor Seroff, Rachmaninoff (London: Cassell & Company, 1951), 188.

[20] Gregory, “Dies Irae,” 138.

[21] Gregory, “Dies Irae,” 138.

[22] John Rink, “Opposition and Integration in the Piano Music,” in The Cambridge Companion to Brahms, ed. Michael Mosgrave (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 95.

[23] Rink, “Opposition and Integration,” 97.

[24] Paul Berry, “Concealment as Self-Restraint,” in Brahms Among Friends: Listening, Performance, and the Rhetoric of Illusion, ed. Paul Berry (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 336.

[25] Berry, “Concealment as Self-Restraint,” 334.

Works Cited

Berry, Paul. "Concealment as Self-Restraint.” In Brahms Among Friends: Listening, Performance, and the Rhetoric of Illusion, edited by Paul Berry, 332-352. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Boyd, Malcolm. “‘Dies Irae’: Some Recent Manifestations.” Music & Letters 49, no. 4 (1968): 347-56. http://0-www.jstor.org.library.juilliard.edu/stable/732291.

Chase, Robert. Dies Irae: A Guide to Requiem Music. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Gregory, Robin. “Dies Irae.” Music & Letters 34, no. 2 (1953): 133-39. http://0www.jstor.org.library.juilliard.edu/stable/730837.

Greitzer, Mary Lee. “Becoming Bach, Blaspheming Bach: Kinesthetic Knowledge and Embodied Music Theory in Ysaÿe’s ‘Obsession’ for Solo Violin.” Current Musicology, no. 86 (Fall 2008): 63-78.

Grove Music Online, s.v. “Breve,” by John Morehen and Richard Rastall, accessed Dec. 9, 2018, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/search?q=breve&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true.

Kang, Heejung. “Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse.” DMA diss., University of North Texas, 2004.

Rink, John. “Opposition and Integration in the Piano Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Brahms, edited by Michael Mosgrave, 79-97. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Seroff, Victor. Rachmaninoff. London: Cassell & Company, 1951.

Ysaÿe, Antoine. Historique Des Six Sonates Pour Violon Seul Op. 27 D'Eugène Ysaÿe. Brussels: Edition Ysaÿe, 1968.

Ysaÿe, Antoine. Ysaÿe: By his son Antoine. Translated by Frank Clarkson. Great Missenden, England: W. E. Hill, 1980.

Zhang, Ying. “A Stylistic, Contextual, and Musical Analysis of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43.” DMA diss., Rice University, 2008.

Copyright © 2019 Alice Ivy-Pemberton